Nobody tells you that it will be red. Bright red, like lipstick or foil-covered Valentine’s Day hearts. We all watched as it left the syringe, traveling slowly but unstoppable through flaccid thin tubing. My eyes pooled with tears as it inched toward its destination, and I held my breath as crimson entered the port beside my daughter’s heart. Mercy’s first chemotherapy drug had been given.

There’s a lot they don’t tell you about cancer. Like the fact that you get a notebook with temperature charts (you will learn to read Celsius) and diagrams of port options and pages upon pages of “educationâ€. You will actually have scheduled visits and an assigned nurse for “education†and you always bring your notebook. The notebook (which we named the “How to Have Cancer Notebookâ€) contains page after page of SO many phone numbers and all the scary reasons you will use them. And you will use them.

Nobody tells you that when you have cancer, you don’t have a doctor you have an army. Yes, there will be one oncologist you see when diagnosed and who creates your treatment plan, but after you meet her you are embraced by a steady stream of fellows and residents and dieticians and nurse practitioners and social workers, chaplains, and attendings (you also learn the very confusing hospital hierarchy of rank and relationship and title). You will revere your oncologist, because she is superhuman. And she is so gentle, so thoughtful, so kind. And so incredibly smart! She will let slip one day that she has a child at home doing online kindergarten, oh and a toddler too. And you will almost pass out in awe of how she does what she does (it will be much later that you learn that her husband is also an ER doc, and you will simply marvel).

You will come even closer to passing out when they explain port placement and how it works (because your daughter will ask SO MANY questions!) and you will have to put your head down between your knees at least once. Then after a while, the bump in your daughter’s throat, and the bulge from the port, and the weekly “accessing†becomes routine, and putting Glad Press’N Seal on your child each week feels perfectly normal. There are so many boxes of Press’N Seal everywhere: in the clinic, on the hospital floor. You might even create an “I Spy Press’N Seal†game with your daughter as you walk laps through the cancer wing.

Nobody tells you how time works differently when you are in the hospital. Hospital stays are at once a slow crawl and an absolute blur. Rounds are a daily parade of masked faces moving in formation from room to room. This hallway army is bigger than you imagine: pharmacist; social worker; resident; attending; your nurse; the charge nurse. And if I am completely honest, there is also almost always at least one hallway soldier whose role I cannot identify. Each provider has their own computer they push along with them and there is a little bottom cubby where they all keep their coffee. Every morning the crowd appears: most stand in the hallway outside your room (COVID), while a few hover bodiless on iPads that are pushed around on little stands (also COVID).

One morning the pharmacist was talking to us from one of those little screens about some disturbing side effects Mercy was experiencing from some medications and his cat climbed up into his lap and looked right at me. I laughed out loud and talked to the cat and found delight in the realization that pharmacists are living through a pandemic and the dynamics of working from home too. When they are finished, they move on to the next room, someone pushing the disembodied pharmacist along as they go.

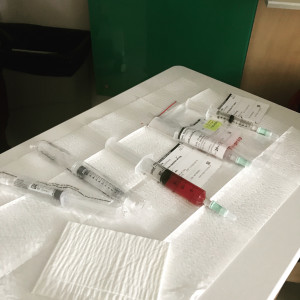

Nobody tells you about the chemotherapy flight check routine. When all of the pre-chemo meds are administered, and the IV bags are hung and it is time for the poison to be delivered, your nurse will call for a “secondâ€. With the beginning of each of the four syringes, another nurse comes into the room and together they check and double-check the dose and speed and label of the poison, performing a complicated call and response. Chemotherapy is toxic, of course, so they will both gown-up each time, and there will be red “danger†stickers on everything, from the IV pole to the entrance to your room. Some chemotherapy drugs require brown shiny bags hung over them because apparently, they can be damaged by the light. This deadly poison has its own kryptonite.

Nobody tells you how you will live and die by numbers. Blood counts, blood pressures, heart rates (did you know you can endure a resting heart rate of 38), and the number of cups of tea consumed each day. You drink tea because the taste of plain water is excruciating. You drink a lot because your “ins and outs†will be an important discussion topic each morning during the hallway gathering. For once, the number on the scale compels a different sort of fear: a dietician will soberly describe to you how feeding tubes work, how they are placed, and how many ounces away you are from needing one. This will motivate you to endure eating, even when it is the last thing you want to do.

Nobody tells you that your home will take on the contours of cancer in surprising places: cupboards intended for dishes and glasses become crowded with prescriptions. Refrigerators are stuffed with boxes of fertility shots, followed by bottles of synthetic THC, and finally loaded down with giant silver pouches filled with IV fluid bags which you are told to refrigerate (though the nurses at the hospital think this is strange). You learn to pull the fluids out an hour before hooking your daughter up to the IV pump you have charging beside the InstantPot to minimize how much and for how long she will shiver and shake.

Nobody tells you about entry into the Cancer Club. It’s not a club anyone wants to be in, but its members welcome you with open arms. You will make connections near and far, via Facebook, the waiting room, and Twitter. And people will be tender with you, and they will tell you the truth. There is a solidarity born from infusion bays, and ANC counts and hairless heads. The clinic, while scary at first, becomes a safe space where you can be understood without saying a word. There will be those you think might be your lifeline who go dark while others, perhaps more distant, draw near and offer themselves with that bowel-moving compassion the Bible tells us that Jesus felt. They will trust you with stories about how it was with their wife; their child; their husband. You will share freely your own struggles and pain, and you will thank God for these friends, daily.

Five months ago I sat inside Family Consult Room #2 in the Surgery department at Children’s Hospital and waited for the surgeon to come in and report on Mercy’s biopsy surgery. My chest hurt and my stomach tightened with every minute that passed. I frantically texted Doug and my Mom: “They told me the surgeon would just call. I don’t know why they put me in a roomâ€. The door finally opened, and the kind and direct surgeon sat across from me and informed me that surgery had gone well and there had been no complications: “We didn’t have to cut her collarboneâ€, he reported. Then his tone shifted. “My policy is to tell families everything that I know, and the rapid lab test we do during surgery came back positive for Lymphoma. Pathology will confirm this in a couple of days, and it is possible that the diagnosis could change, but I wanted you to know what I know.â€

Nobody tells you what it feels like when those words travel, slow motion red, into your heart and set your life on fire. My daughter has cancer.

Wow! Tears! Well written and heartbreaking.